Punjab's Extreme Monsoon: Impact on Basmati Rice Exports

When the Rains Don't Stop

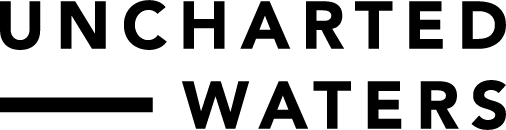

August 2025 brought extreme rainfall to Punjab, India's premier Basmati rice region, triggering widespread flooding across districts that produce the aromatic rice variety prized in international markets. The monsoon season started early with heavy May rains and remained persistently wet throughout the growing period. August precipitation reached almost double the 15-year average in some districts, with the most intense rainfall concentrated in the final week—disrupting the critical mid-season growth phase.

The blue shading in satellite data shows how exceptional August precipitation was compared to historical patterns, with extreme rainfall focused in key rice-growing areas like Amritsar district. ERA5 climate data reveals 3 to 6 times more intense rainfall events, measured by days exceeding 30mm, 50mm, or 80mm daily precipitation thresholds.

Figure 1 Monthly precipitation over India, compared to the historic average over the past 15 years (left). Forecasts represent expected precipitation based on current ENSO and IOD status. Extreme precipitation (blue gradient) is shown over north-western Indian, in red box, with quantiles indicating how often this amount of August precipitation is exceeded over the past 15 years (right). Source: ERA5

Assessing the Impact

It's too early to determine the exact impact on India's overall rice production and prices. While Punjab experienced severe flooding, other major rice-producing regions like Madhya Pradesh in central India and Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh in the south also saw above-average rainfall but with less severe flooding. When disaster strikes one region, neighboring areas with better water availability sometimes benefit from improved growing conditions. Rice, due to its distinct cultivation practices in flooded paddies, can tolerate intense rainfall better than other cereals—though even rice has limits when fields remain underwater for extended periods.

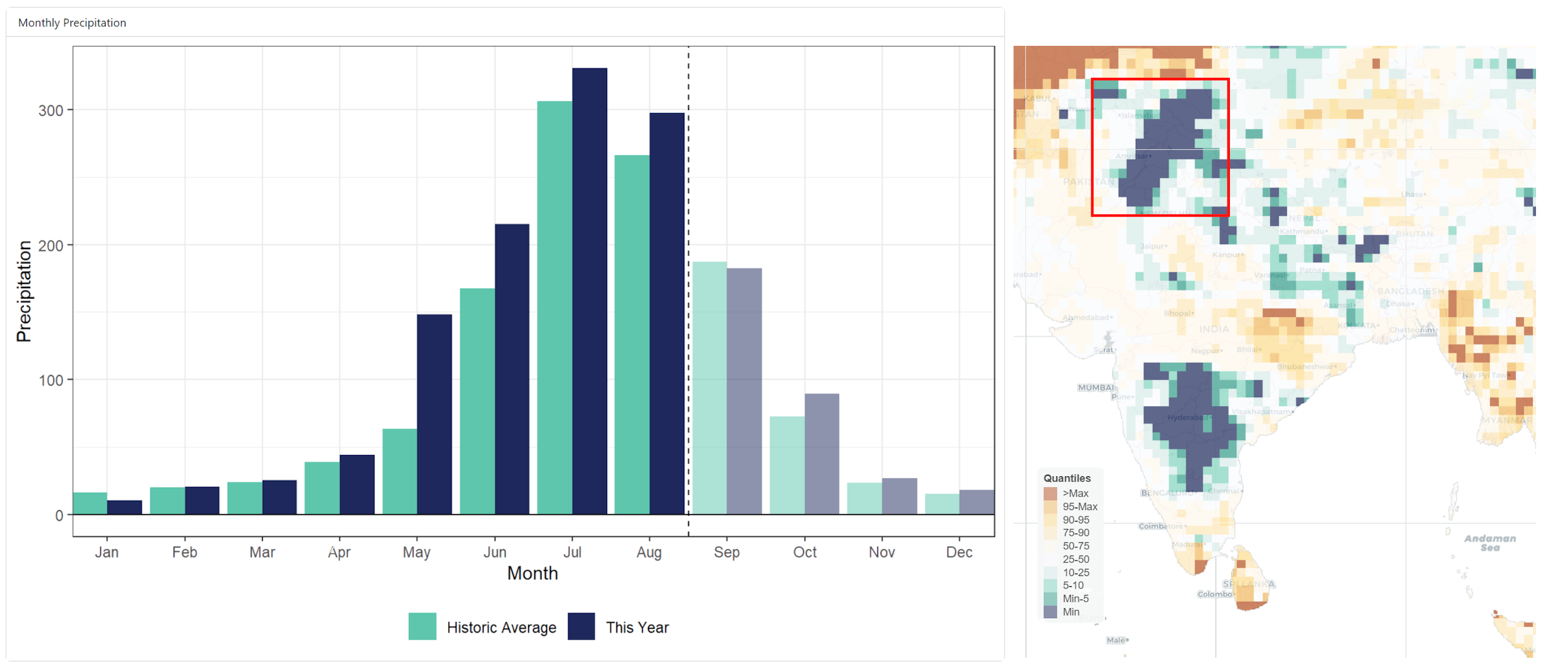

Punjab remains the state with the highest rice yields in India, approaching 7 tons per hectare. However, other states have been catching up rapidly. Just fifteen years ago, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh yields remained below 2 tons per hectare. They have since doubled. Uttar Pradesh and Telangana have now overtaken Punjab in total production volume, reducing Punjab's relative importance to national supply.

With harvest about to begin, the full impact on domestic prices and export volumes remains to be assessed. Better yields in other regions might partially compensate for Punjab's losses, maintaining overall production levels despite the localized flooding.

Figure 2 Yields (ton per hectare) for selected Indian states. In some, increase is accelerating (in red), in others it is linear.

MP = Madhya Pradesh, UP = Uttar Pradesh, TG = Telangana, PB = Punjab. Source:Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Govt. of India

India's Evolving Role in Global Rice Markets

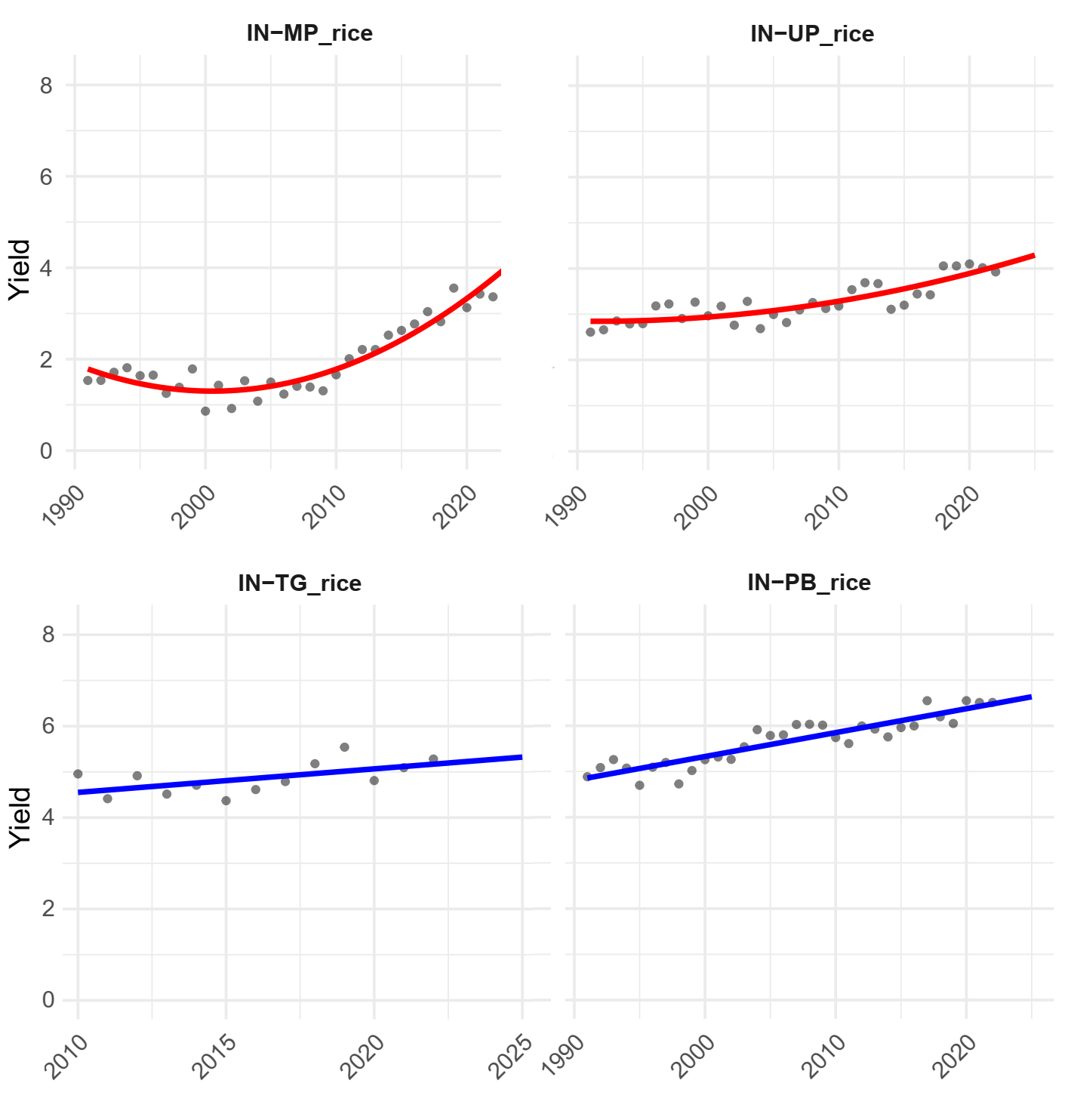

The Punjab floods matter particularly for global rice trade. Punjab is a major Basmati rice exporting region, and damage to this premium crop variety has outsized impacts on international markets even when India's overall domestic rice supply remains adequate. India has transformed from a primarily self-sufficient producer—occasionally importing small quantities during deficit years—to a net exporter in recent years through substantial yield and production increases.

However, production must keep pace with population growth. Below-average harvests have repeatedly led to export restrictions that ripple through nations increasingly reliant on Indian rice. India's position as a "pivot" in global rice markets means its domestic weather events can trigger food security concerns thousands of kilometers away, particularly in the Middle East and West Africa where Indian rice represents a significant share of imports.

This volatility reflects a broader challenge: as yields increase and India becomes a more important exporter, the country's exposure to weather variability creates larger disruptions in global markets when extreme events occur. The same progress that enables export growth also raises the stakes when monsoons fail—or when they don't stop.

Figure 3 Major rice producing countries, as expressed in energy content (kCal per year). For food use only (corrected for feed and other uses). Average over 2010-2025. Source: Uncharted Waters, using FAOSTAT data up to 2022 for calibration

Figure 4 Imports and exports of rice for food use. Blue regions are net exporters—countries producing more food than they consume. Red regions show nations depending on imports. Average over 2010-2025. Source: Uncharted Waters, using FAOSTAT data up to 2022 for calibration

Figure 5 India’s import and export. Blue lines and shading show major destinations for Indian rice, red minor imports. Average over 2010-2025. Source: Uncharted Waters, using FAOSTAT data up to 2022 for calibration

Climate Volatility: The New Normal

Recent years have seen multiple rice crises across Asia. Japan faced shortages requiring emergency imports from South Korea for the first time in over 25 years, with ministers being sacked over the crisis. Indonesia battled drought-driven production declines. India itself has oscillated between export bans during poor harvests (2022-2024) and resuming exports when conditions improve.

The common thread: increasingly erratic weather patterns making it harder to rely on historical climate data and lived experience to predict growing conditions. This is precisely why real-time monitoring and analysis has become essential for food security planning.

What we're observing in Punjab—extreme precipitation events concentrated in short periods—fits the broader pattern of weather intensification. These aren't simply "bad years" to be weathered until conditions return to normal. The variability itself is the new normal, requiring different approaches to agricultural planning, water management, and trade policy.

Supporting Timely Decisions

Uncharted Waters monitors these impacts in real-time, tracking how weather events affect crop production and analyzing how disruptions in one region cascade through global food supply chains. We partner with Wageningen Environmental Research (www.wur.nl) and, in India, with WOTR (www.wotr.org) to assess climate impacts on water and food systems.

Our digital twin of the global food system integrates process-based crop modeling with machine learning to provide monthly updates on weather events, recent harvests, and expected production. By monitoring stocks and trade flows in real-time, we deliver market insights before observation data becomes available—helping organizations from local NGOs supporting farmers to businesses exposed to agricultural commodity volatility make informed decisions faster.

In India, WOTR is integrating our data into advisory services reaching 1.2 million farmers through their network. Early feedback from 500 pilot users shows positive reception of enhanced climate information for farming decisions.

As extreme events occur more frequently and their impacts spread wider, timely insight on current production and expected supply becomes crucial for anticipating tipping points and managing uncertainty effectively.

Uncharted Waters analyzes how climate events and water availability affect crop production, food supply, and ultimately food security. We connect food shortages in regions impacted by extreme weather to the export capacity of countries with surplus production.

This analysis represents our current understanding and predictions may change as new information becomes available.

This work was supported by the Kyeema Foundation.