Central Asia's Snowpack Crisis: Real-Time Data Reveals Urgent Water Security Threats

Central Asia's mountain snowpack reached critically low levels in 2025, with smaller tributaries losing over 50% of their minimum snow cover compared to two decades ago. While major rivers maintain flows through increased glacier melt, this temporary stability masks a looming crisis for millions who depend on seasonal snowpack for water security.

In our latest analysis published in Climate Impacts Tracker Asia, Uncharted Waters and leading water experts from Uzbekistan's Tashkent Institute of Irrigation and Agricultural Mechanization Engineers (TIIAME-NRU) reveal an ongoing decline in snowpack across Central Asian watersheds reducing river flows and water availability for irrigation and other uses.

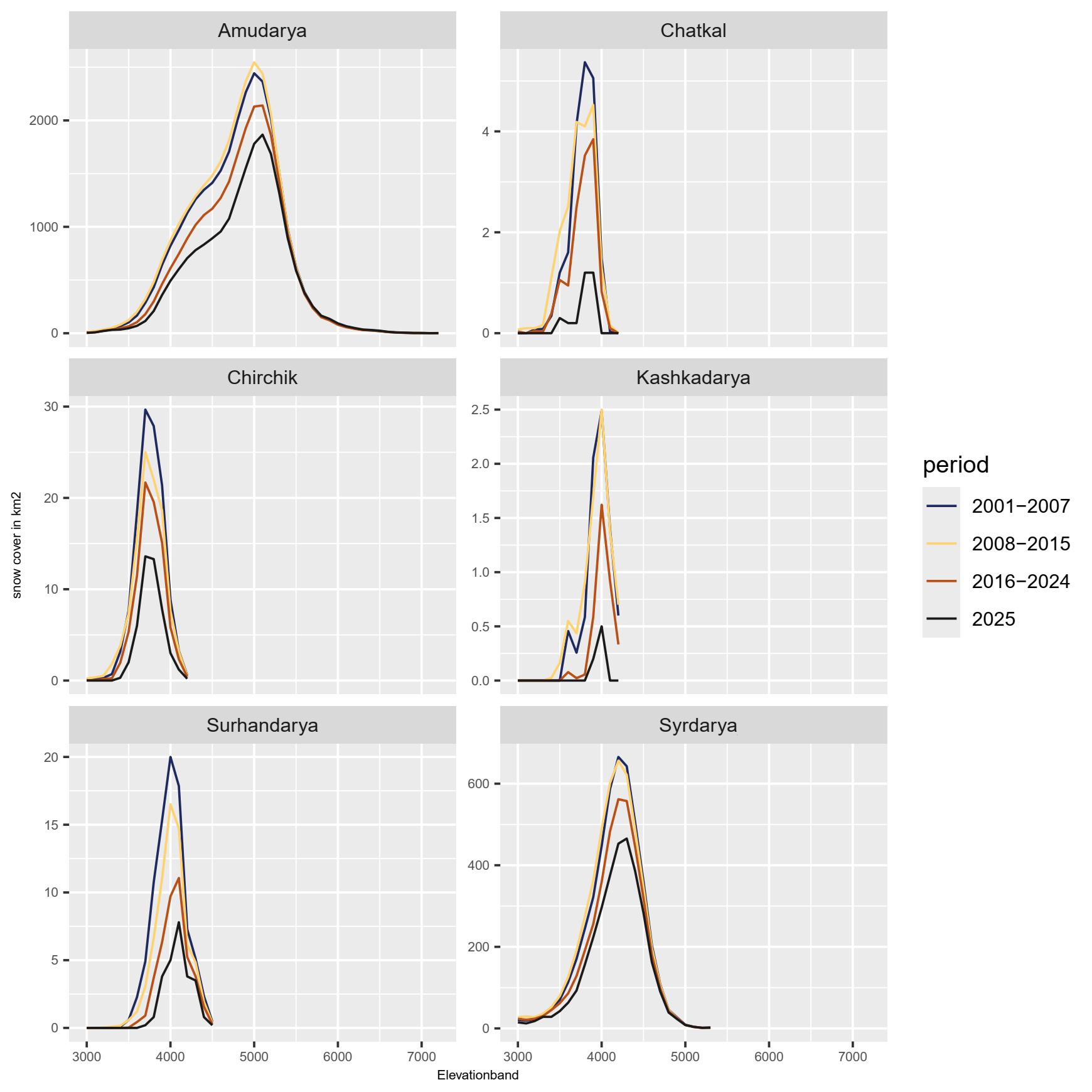

Dramatic declines in smaller tributaries

The smaller, lower-elevation tributaries are experiencing the most severe impacts. The Surhandarya basin, which supports agriculture in southern Uzbekistan, has seen its minimum snow cover plummet by 51% compared to the 2001-2007 period[1]. The Kashkadarya shows a 54% reduction, with 2025 data showing the basin retaining only 0.7 square kilometers of snow cover—essentially bare. The Chirchik River, flowing near Tashkent and supporting the capital region's agriculture, has lost 31% of its minimum snow cover. The 2025 measurement of 47.4 square kilometers represents less than half of what was typical just a decade ago.

The region's water dynamics present a paradox that masks the severity of the crisis. The major rivers—the Amu Darya and Syr Darya—maintain relatively stable flows, benefiting from increased glacier melt in their upper reaches. This year, the Amu Darya basin still retains about 19,500 square kilometers of minimum snow cover, despite representing a 29% decline from the 2001-2007 average. However, he smaller tributaries, which depend more heavily on seasonal snow accumulation rather than glacier melt, are already in severe decline. Even basins that showed slight increases in 2008-2015, like the Chatkal, have collapsed to minimal coverage—just 3.1 square kilometers in 2025.

Figure 1 Minimum snow and glacier cover in summer, by elevation, for 2025 and three previous periods

2025 drought

Precipitation from January through spring ran 30-70% below average every month, with only June showing near-normal rainfall. Spring temperatures exceeded the 15-year average, accelerating snowmelt when water should have been stored as snow for gradual summer release. With the arrival of autumn in the high mountains, snow cover remains far below normal—a pattern that breaks from typical seasonal accumulation.

Figure 2 Seasonal snow cover pattern. While winter snow cover holds up reasonably well, this snow melts earlier and faster, resulting in a much longer period without significant meltwater contribution in the lower tributaries at a time when water demand is high.

For Uzbekistan and its neighbors, the message is clear: traditional water management approaches based on historical abundance must give way to strategies built for scarcity. Every drop counts when the mountains no longer hold their water in reserve.

Read the full analysis: ‘Central Asia's Vanishing Snowpack: A Real-Time Crisis Unfolding in 2025’ in Climate Impacts Tracker Asia.

This analysis continues our ongoing collaboration with Prof. Abdulkhakim Salokhiddinov and Andrej Savitskiy at TIIAME-NRU, combining real-time satellite monitoring with deep regional expertise to provide decision-relevant insights on Central Asia's evolving water crisis.

[1] 2016-2024 versus 2001-2007 average